XXV. FUNERAL RITES IN THE NORTHERN BASQUE COUNTRY

Since the 1950s, the traditional funeral rite has undergone far-reaching changes in Iparralde and continues to do so at an ever-increasing rate. Some of them, already irreversible, are above all testament to a social order and a view of the world that are very alien to the new generations. However, a significant part of the rituals survives, but they are often mere “points of reference” and “organisational frames” lingering in people's memory. But for how long?

Since the 1950s, the traditional funeral rite has undergone far-reaching changes in Iparralde (the part of the Basque Country within France) and continues to do so at an ever-increasing rate. Some of them, already irreversible, are above all testament to a social order and a view of the world that are very alien to the new generations. However, a significant part of the rituals survives, but they are often mere “points of reference” and “organisational frames” lingering in people's memory. But for how long?

The coastal strip can be seen to have totally broken away from the inland area. There, death is dealt with outside the context of the home, etxe, and of the framework that forms a neighbour-based society. As regards Christians, here more than anywhere else, they have to embrace their faith in the midst of indifference, in the best of cases.

These are the three avenues that we have explored and particularly the first, namely, the state of the current funeral rite in the mountains, the lowland areas inland and the coastal strip. We have focused on painstakingly describing the practices and its versions; we have sought to highlight relations between individuals and between situations (in order to see how the neighbourhood-based society that underpins our culture is expressed, but which today, has not awoken any interest in the ethnology of Iparralde). We have explored the urbanised environment along the coast in its more advanced aspect on the way to “modernisation”. We have here and there noted recent changes, but our intention has always been to portray the world in which our parents still conducted their daily lives; that is the testament that we sought to build, as a solid pillar, and to which we dedicate the summary.

Page content

- 1 Omens and signs, dying

- 2 Christian care

- 3 Beliefs surrounding death

- 4 Family and household morning

- 5 The announcement

- 6 Preparing the funeral cortege

- 7 The funeral cortege

- 8 Make up of the cortege and order

- 9 Offerings

- 10 The burial

- 11 The homestead and the “funeral feast”

- 12 Mourning

- 13 Legends around death

Omens and signs, dying

Death is the natural end to a long life. Old people would become a cause for concern for some time. The priest would visit them more often, the immediate neighbours ask about their health and visit them. Everyone would get ready for the fatal outcome.

Death knocks suddenly where it is not expected, at an unforeseen moment. A type of resignation, of fate (jin beharra, gertatu beharra zen) as if our destiny were already written. Exacerbating this concept, the person who dies shows us that there is in something in us that transcends us; as captured in that well-known saying: odolak baduela hamar idi parek baino indar gehiago. Finally, there was Herioa, the grim reaper, who was believed to come and find the dying, but they did not give up the struggle easily: anyone who was weak would fall easily. That fight was followed by the community with concern (particularly if the ill person was young), and they would speak matter-of-factly of running out of time, of fighting, of remission, of strength, etc. In addition to that context, to which the discourse of the Church would have to adapt, there was a “reading of the signs”.

The latter are essentially of two types: 1) abnormal, incongruous events (coincidences, “mishaps” particularly at night); 2) warning signs by nature and, more specifically, by animals. The signs warned the people who knew how to read them: laster norbait hilen da. Therefore, it was essential to know how to read the sign of a curse, the evil eye, belhagilea, and other spells, konjuratze, wanting the death of so-or-so, herioa desiratzea.

Finally, there are grounds to believe that the dead continued to be active among many of our compatriots back in “old times” in the form of errant souls, arima erratiak. Real beings of a middle world, those still active errant souls, dwellers of the shadows, but also of the fugitive flicker, of the deeply exhaled breath, would only enter with great difficulty in the antechamber that the Church prepared for them to wait that great judgement that would presumably by the last. There was a widespread belief that even though the dead left, they did not necessarily disappear. Ultimately, the Church could not contradict this idea and would rather embrace it by giving it a special meaning (thus, God converts the dead child into an angel).

Dying has led to customs that highlight the public status around the death. In principle, this is where the nun sacristan, andere serora, a key person of the traditions alongside the ecclesiastical ritual, came into play. She was in charge of tolling the church bells and that message had a double meaning, to: 1) notify the community of the living (including the animals and nature that marked the passing, “they were idling”); 2) help the dying “comforting them”, “helping them to leave”. The dying person thus knew that, during that time, he was the centre of all the attention and care and that the prayers were being offered up for him. Nobody died alone or abandoned.

Christian care

There is nothing original in this regard as the viaticum and extreme unction are practices defined by the Church. Both mark the start for the dying person of the time where he will unite with the Mystical Body of Christ, that uninterrupted solidarity that will last for eternity and be continuously revived by worshipping one's ancestors.

That care also clearly means that that the time has come for each of us to put our deepest thoughts in order and to attune with other realities. Therefore, it was a dreaded moment and the priest was often called too late, as they did not want to “scare” the person who was dying by making him face that terrible end awaiting everyone.

Beliefs surrounding death

It is very difficult to comment on this theme. Apart from the Christian (the will of God, Jainkoaren nahia) or fatalist (azken arena, azken ozka...) angle, death “lives” as a presence and as a departure. In fact, they are interpretations based on signs, on ways of acting that seem to have been commonplace back in the past.

The presence refers to Herioa. When the grim reaper came to take the person, everyone had to be on guard and the animals would be put in the barn. That arrival could leave a mark that fire would delete, would purify.

The departure is that of the “soul” or of the “spirit”, izpiritua, arima, which accompanies the last dying breath, azken hatsa. Accordingly, a tile would sometimes be taken from the roof and the window or door of the room where someone has just died continues to be opened. The deceased has left us, joan zauku, but his corpse was not considered to be harmless and the eyes had to be closed as soon as possible to avoid it calling someone. The expressions collected to describe that passing reveal a complex, disperse world and also full of nuances. Naturally, the Christian vision, as imposed by the Church, played its part fully. From that viewpoint, death is separation, but also being brought before the highest court and access, admittedly not guaranteed, to a heaven where a God reigns who holds us accountable.

Family and household morning

Women, until relatively recently, were entrusted with the household rite, helped by the neighbours and particularly the first neighbour, lehen auzoa. Meditation, silence, the wake and visits marked that time that was the start of the mourning period.

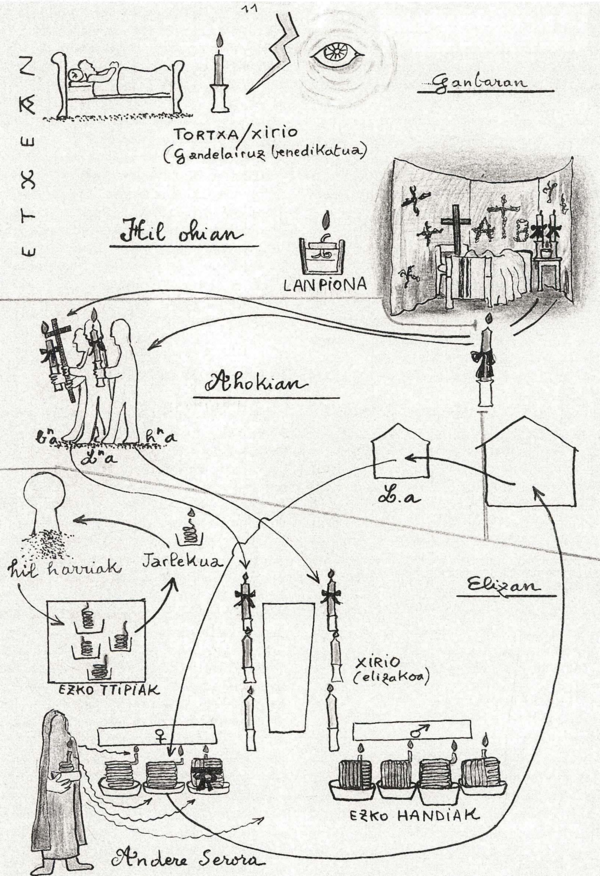

The corpse was washed, dressed and laid out on a bed, which was sometimes decorated. The room was prepared by covering the mirror, changing the candleholders and place settings, etc.; the cross that the first neighbour had collected from the church was placed on a seat covered with a special cloth, lonjera. A dish with Holy Water and a Palm Sunday palm would be placed on a table to bless the deceased during the visits. A candle would be lit beside a crucifix or and an image of Our Lady on the bedside table. The presence of that light was essential and we have striven to differentiate between the types of “candles” and lights, along with their relative value at certain times and in different circumstances.

The announcement

The first neighbour was notified and he would, in turn, be entrusted with informing the local council and the parish priest. The nun sacristan would usually hand the first neighbour the funeral cross and he would respectfully carry it to the room of his neighbour; meanwhile she would toll the bell to tell the village and surrounding areas. A certain “code” was often followed depending on whether the deceased was a man, woman or child.

The first neighbour, sometimes along with the second (those neighbours are defined according to criteria that we have sought to specify), would meet with the family and draw up the list of relatives to be told. The first neighbour distributed this task among his neighbours and other locals if needed, who thus became death's harbingers, hil mezukari; he would undertake the longest journey. The announcement, hil abertitzia, would let people know about the death and indicate the date of the funeral. Some animals (cows, sheep, bees, dogs) would also be told of the death and that would be left up to a member of the family. Some of those animals could mourn for a considerable length of time, particularly the bees and ewes: they were kept in the burn, their bells were kept silent or a cloth was placed over them.

And finally, the announcement was echoed with the death knell tolled three times a day, at dawn, at midday and at night: argitzian, eguerdian, ilhuntzian.

Preparing the funeral cortege

A new character, the carpenter, would then be involved and was in charge of organising the funeral in many places. He would place the deceased with the help of one of his helpers or of the first neighbour in the quickly fashioned coffin. As custom would have it, the family did not handle the body or be present as the body left. The deceased was usually wrapped in a shroud, sometimes with its head on a small cushion; the corpse would be dressed in its best suit or dress. With shoes on its feet and a beret on its head, it was ready to set off. It was then the eve or the morning of the funeral.

The coffin was an aedicula made up of canvases decorated with branches. In Lower Navarre, the carpenter built in the hall, eskaratze, against the main door, a small chapel with canvases that the female neighbours decorated with green branches (boxwood, bay). The background canvas, known as hil mihisia, was special. The carpenter places the coffin on two chairs in the centre of this closed space. Candles in holders provided by the family or borrowed from the neighbours (each homestead wrote its name on the base to then get it back later) were placed on each site. Two symbolic items were important: a marble crucifix bought by the first neighbour (which would be placed on the funeral monument), along with the house's ezko (mourning candle used in the church during the funeral masses).

In general, the first neighbour wife, accompanied by her husband, welcomed the visitors at the entrance to the hallway. She took the relatives to the kitchen where the residents of the house would be.

As the time of the funeral approached, the women neighbours would help the women to put on their heavy capes, and would help the men to fasten the mourning capes and with their ties.

The funeral cortege

The carpenter would organise the cortege as it left the house and handed out candles and flowers. The male first neighbour would usually lead the cortege, carrying the funeral cross from the church. He was followed by the priest and then the corpse, carried by its four “first neighbours”. The women were behind the female first neighbour who carried the light, argizaina, in Lower Navarre, with the candles of the first neighbours in a large round basked.

The funeral cortege was usually in a single file, with the family following the deceased, with the men separate from the women. During the journey to the church, other mourners would join the cortege at the end in no special order.

Everybody used the corpse way, hil bidia, which was the path from the house to the church.

Make up of the cortege and order

There was great variety in this regard and which could even be found in the funeral attire and the way of wearing it. This last point was particularly obvious in the case of men, which is however, the most passive aspect, if not the most insignificant, within the ritual.

This theme is highly complex as it reflects local practicalities: there were rituals found throughout Zuberoa, and other very motley ones turned Lower Navarre into a patchwork of particularities. However, the neighbours were the backdrop everywhere to the pomp of the funeral cortege, where the Church clearly had a place, but only its own. This beautiful staging of the drama and pain experienced jointly as a community evoked the pomp of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The funeral

On leaving the house, etxe, the carpenter organised the cortege, at least in Lower Navarre. On entering the church, the andere serora would meet it. The former represented a community marking the death of one of its own and the latter that same community who received it in a place where, by means of the liturgy, the Church would give its real meaning to death and therefore to life.

There was little variety in the funeral mass. Its most notable traits belonged to a type of “domestic” religion. They clearly appeared in the following aspects: 1) Importance of the nun sacristan who was the “mistress of ceremony”; 2) Role and active presence of the female first neighbour; 3) Seating of the people and particularly the women in the oldest tradition; 4) Use of lights, according to their different types (ezko, xirio).

Offerings

This section has to first mention the trade-off between neighbours, ordaina. Masses were said for the deceased; each home along with each close relative would do so. That offering would usually be in keeping with the degree of kinship, with the wealth of the person making the gift, as well as being on a reciprocal basis reflecting the importance of a gift make by the family of the deceased on a similar occasion. Thus, solidary was expressed by this offering that was usually collected by the first neighbour or, as applicable, the carpenter or the master cantor, chanter.

The list of people and homesteads making an offering was published on the church door. In earlier times, the priest would read it from the pulpit.

The light offerings have already been mentioned. Subsequently, the family's dead would be regularly and collectively remembered by masses being said, particularly those offered by women.

The burial

It seems that the oldest custom only required the first neighbour, along with the other coffin bearers (who usually would have dug the grave), to accompany the priest and be present at the burial. Once the grave was closed, the first neighbour would go and find the family and the cortege to take them to the graveside. A final prayer would be said and the people would leave.

The homestead and the “funeral feast”

In Lower Navarre, as the cortege returned to the house, the people would pause by a fire lit in front of the door, where the people would stand in a circle and say a prayer. The funeral repast was held in the eskaratze set up by the carpenter, who was in charge with handing out bread, wine and sometimes coffee. In fact, that meal could be simple, but could also be similar to a real feast.

Generally, the meal ended with a prayer, said by the master cantor or the first neighbour, or even the priest if invited. The prayer could be only dedicated to the deceased but the other dead of the home were sometimes included, etxetik atera diren arimentzat, along with the first of the people present who would be going to die. Those last two cases clearly expressed solidarity and a link between the here and now and that other place that welcomes our souls.

That all occurred at the homestead, thus bringing the cycle to an end.

Mourning

The social conventions of the time were very important during the mourning period and established the way of behaving. The mourning period was marked by external signs that would gradually fall into disuse (except in the case of our grandmothers, amatxi, who wore black as long as we could remember); the length of that period and its intensity particularly depended on the nature of the deceased (child, adult) and the link with them.

The earliest periods of mourning seemed to involve ceremonies organised by women. There were also “neighbours' masses”, which the people surveyed could barely be remembered. Those ceremonies were less frequent from urthe buruko meza, the traditional “year-end mass”.

Legends around death

There are no “legends” about death as such in this territory, and at best, just some stereotypical stories about arima erratiak, along with clichés and practices beyond any seeming rationality. It was unusual for Herioa to be seen as an entity and for one of the people interviewed to describe it as such. A deep-rooted and structured funeral ritual makes the fatal moment is equivalent to the passing of the home, etxea, to the eternal abode.